Tests

Aiken has first-class support for unit tests and property-based tests. This means that you can write tests in Aiken directly and execute them on the fly. Hence, the toolkit (aiken check) can parse tests, collect them, run them, and display a report with (hopefully) helpful details.

Unit tests

Writing unit tests

To write a unit test, use the test keyword:

test foo() {

1 + 1 == 2

}A unit test is a named function that takes no arguments and returns a boolean. More specifically, a test is considered valid (i.e. it passes) if it returns True.

You can write tests anywhere in an Aiken module, and they can make calls to functions and use constants the same way. One exciting thing about tests is that they use the same virtual machine as the one for executing contracts on-chain. Said differently, they are snippets of on-chain code you can run and reason about in the same context as your production code.

Unit test reports

Let's write a simple function with some unit tests as an example.

fn add_one(n: Int) -> Int {

n + 1

}

test add_one_1() {

add_one(0) == 1

}

test add_one_2() {

add_one(-42) == -41

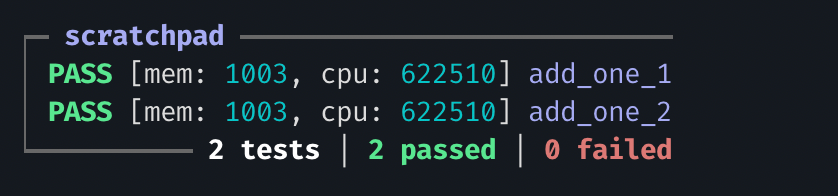

}Running aiken check on our project gives us the following report:

As you can see, the report groups tests by module and gives you the memory and CPU execution units needed for each test. That means tests can also be used as benchmarks if you need to experiment with different approaches and compare their execution costs.

Tests can be arbitrarily complex; unlike on-chain scripts, they do not have any execution limit -- or, more specifically, their limit is sufficiently large.

Automatic diffing

Aiken's test runner is (trying to be) intelligent and helpful, especially on test failures. If a test fails, the test runner will do its best to provide information about what went wrong. This is particularly efficient if you write your tests as assertions using binary operators (==, >=, != etc..).

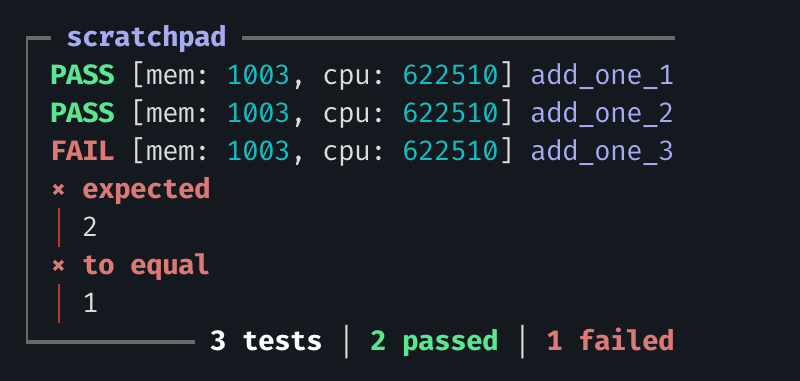

For example, let's add a failing test to our example above:

// ... rest of the file is unchanged

test add_one_3() {

add_one(1) == 1

}

Brilliant! We get to see what both operands are evaluated to, and the test runner points us to the problem.

Property-based test

Short introduction

One of Aiken's unique selling points is its property-based testing framework with integrated shrinking. Property-based testing is the art of generating test cases by exploring the realm of possible inputs and looking for general behaviours rather than specific cases.

For example, if you consider a function list.reverse that reverses the order of elements in a list, it has an excellent property: calling it twice puts the list back in its original order. You can approach testing that function by generating random list samples and checking that they satisfy the property.

If a counterexample to the property is found, the framework tries to simplify it to a minimal counterexample so that it is easier to digest and reason about. This is a crucial step since exploring an input domain randomly can lead to arbitrarily large sample values that may obfuscate the real problem. Imagine a function that operates on a list of integers and fails for negative integer values. In this example the list [12, 441, 0, 7863, -2, 1213] is a valid counterexample but [-1] is arguably a much better one. It allows for the precise pinning down of the issue more directly.

In classic property-based testing frameworks, finding a smaller counterexample can be tedious and is referred to as shrinking. Developers writing properties must define how to get to smaller counterexamples from an initial value. In Aiken, the framework integrates and automatically manages this process.

Writing properties

A property-based test is a test with a single argument that specifies a Fuzzer. A fuzzer, or generator, is an abstraction that specifies how to generate (pseudo-) random values from a source of randomness.

We provide -- and strongly recommend using -- a core library for fuzzers: aiken/fuzz (opens in a new tab). This library contains valuable primitives that go through the hassle of abstracting the management of the pseudo-randomness on your behalf so that writing fuzzers becomes bliss. Use it without moderation!

use aiken/fuzz

test prop_is_non_negative(n: Int via fuzz.int()) {

n >= 0

}A Fuzzer is introduced as a special annotation for the argument using the via keyword and must be of type Fuzzer<a> (although a must be instantiated to a concrete type!). In the example above, it is of type Fuzzer<Int>. There's thus a direct relation between the type of an argument and the type carried by its fuzzer! Therefore, the type annotation for the argument is entirely optional since it is redundant with the fuzzer.

Composing fuzzers

Fuzzers can be composed directly inline after the via keyword:

use aiken/fuzz

test prop_list(xs: List<Int> via fuzz.list(fuzz.int())) {

todo

}They can also be defined into separate functions and called by names:

use aiken/fuzz

fn my_fuzzer() -> Fuzzer<List<Int>> {

fuzz.list(fuzz.int())

}

test prop_list(xs: List<Int> via my_fuzzer()) {

todo

}Property test reports

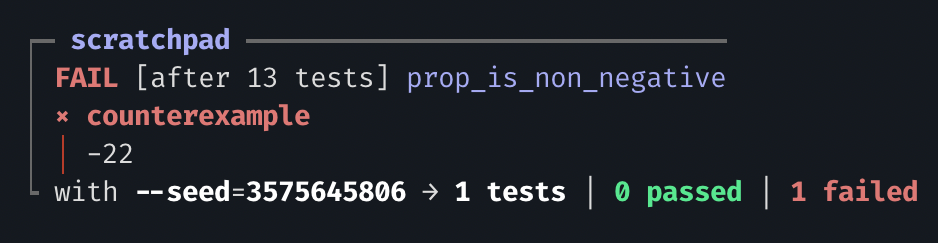

Akin to unit tests, properties are executed using the aiken check command. They provide a report highlighting the number of random samples checked and a simplified counterexample in case of failure. For example, if we run our prop_is_non_negative above operating on int, we get the following:

As you can see, the property is invalidated by negative values generated by the int() fuzzer. The counterexample is shown directly in the test report, along with the number of tests that ran until a counterexample was found.

Labelling

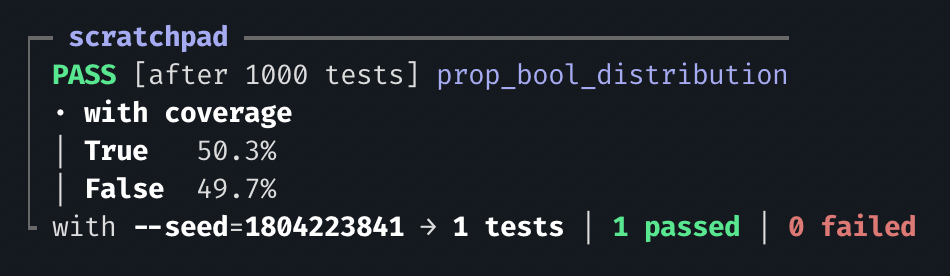

Often, one wants to assess that specific paths are being explored in a random walk. This is particularly true of complex generators that explore a large domain space. The aiken/fuzz (opens in a new tab) library provides labels for that purpose that are automatically gathered by the framework. Upon success, their distribution across all test runs is shown in the report. Labelling can also be useful to assess a fuzzer's correctness, and we strongly recommend testing your fuzzers! A common pitfall of property-based testing is properties that do not actually test anything due to wrongly defined fuzzers. For example, let's inspect the bool() fuzzer from the aiken/fuzz (opens in a new tab) library:

test prop_bool_distribution(predicate via fuzz.bool()) {

fuzz.label(

if predicate {

@"True"

} else {

@"False"

},

)

True

}As we can see, the generator is mostly uniform between True and False (phew!). Note that it isn't necessarily exactly 50% due to the random nature of the sample, but it asymptotically converges towards that.

Note that we have passed the extra option --max-success=1000 to the check command here to increase the number of tests run and get a better view of the random sample.

Testing failures

Sometimes, you need to assert that a particular execution path can fail. This is also known as an "expected failure" and is a valid way of asserting the behaviour of a program. Fortunately, you can do this with Aiken, too, by adding fail after the test name. So, for example:

use aiken/math

test must_fail() fail {

expect Some(result) = math.sqrt(-42)

result == -1

}The fail keyword here works for both unit and property tests, with a subtle difference for property tests. Indeed, a property that is expected to fail will still run multiple times and only be considered successful if ALL the execution of the property failed. This is useful to write non-properties, especially if they rely on fail or expect for checking pre-conditions under the hood. Said differently, a property test flagged as fail will stop at the first successful evaluation and be marked as failed.

For properties, it's also possible to indicate fail once in order to run a property until it fails or until it reaches the maximum number of tries (default to 100). If the test runner finds 100 tests that satisfy a property expected to fail once, the entire test is considered a failure. Said differently, a property test flagged as fail once will stop at the first failed evaluation and be marked as a success. If none of the evaluation fails, it is marked as failed.

Running specific tests

aiken check supports flags that allow you to run subsets of all tests in your project.

Examples

aiken check -m "aiken/list"

This only runs tests inside the module named aiken/list.

aiken check -m "aiken/option.{flatten}"

This only runs tests within the aiken/option module that contains the word flatten in their name.

aiken check -e -m "aiken/option.{flatten_1}"

You can force an exact match with -e.

aiken check -e -m map_1

This only runs tests in the whole project that exactly match the name map_1.